Mastering Stress: Riding Tips for Young Horses

1 min. read time

Audio version – listen to this article easily

Horses are perfectly adapted to life in the wild. Foraging for food is easy – horses practically stand on it as they scan the open grassland for potential dangers. In order for the feed to be digested as soon as it lands in the horse's stomach, the latter constantly produces gastric acid. Today, with horses now in stables and adapted to "human" daily routines, this can become a challenge. This is also true for the second major equine trait: horses are flight animals. These two traits must be strictly observed in daily handling in order to prevent the animals from becoming stressed.

If you only want to look into individual questions on stress, then click on the desired chapter heading and go directly to the answers you seek:

Let's start with the main issue of avoiding stress: horses are creatures of habit, and find comfort in a regular daily routine with fixed times for feeding and exercise. Always present a calm demeanour when working with your horse. After all, you can't explain things to your horse.

Your horse and you live in two different worlds, and while words are important in your world, they don't matter to your horse. Your horse's world is instead defined by sensations. These can be visual impressions, sounds, or even smells. Your horse links these sensations to positive or negative experiences.

For example, if your horse is only put in the trailer when it is taken to the vet, it will have little to no positive feelings associated with the trailer, and little pleasantness waiting at the end of the trip. This only makes loading more difficult. Routine loading and unloading will make the trailer a more commonplace object for the horse. Important: don't forget rewards! And here's something else you have to consider: your horse thinks in pictures, so a person with a hat and the same person without a hat are two different people to your horse. This phenomenon may wear off as he gets to know you better, but if you have a new horse, don't be too creative with your clothing choices.

Relaxed interaction is rarely a problem in everyday life, but therefore all the more important in unusual situations. The classic example is a visit to the vet. Your horse is already feeling poorly, and then has to see the vet on top of that. This is even more important when a trip to a veterinary hospital is called for. In these situations, you must be his moral support.

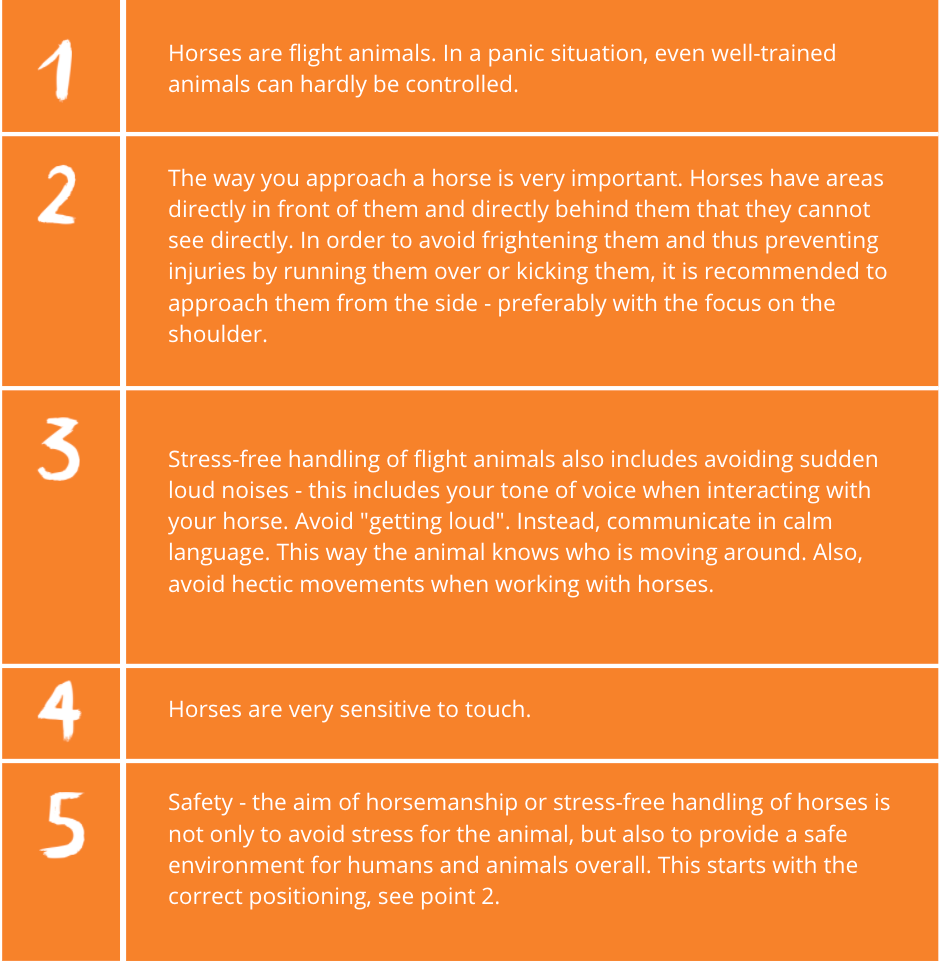

It applies to other situations as well: loud noises (like shouting and screaming) and hectic movements are taboo. Always move within your horse's field of vision; if that's not possible, always make sure that he is aware of your presence. Remember, horses are flight animals. Should they perceive a noise or movement in their periphery as a danger, they will always want to flee. This behaviour ensures their survival. Behaviour that's suitable and encouraged on vast prairies, however, can lead to injuries for humans and animals in far more cramped stalls or trailers. It is also time-consuming. If your horse gets into a proper panic, he will need about half an hour to recover and calm down enough for you to continue working with him. So staying calm also saves time.

A trip to a veterinary hospital will always be stressful, no matter how well you take care of your horse in transit. Occasional stressful situations should not pose major problems, but certain situations can arise in everyday life that cause stress over a longer period of time. Do you have neighbours that you prefer to avoid? Even within herds, it may happen that two horses literally cannot stand the smell of one another. To prevent permanent confrontation, they should be stabled at a certain distance from each other. At the end you will find a basic checklist for optimum stress-free handling of your horse. Following these basic rules in daily interactions is an important aspect of avoiding stress – but of course they are not the only ones.

The equine organism is perfectly adapted to living in pastures. A constant production of gastric acid allows horses to take in feed constantly. Under human care, several challenges lurk at once: A pasture is not always available: during travel, in the winter, or in adverse weather conditions, forage will not be constantly available. Concentrates are another food source – one that your horse will find totally delicious, but they must be used with caution. Basically, there must always be enough high-fibre roughage available for the constantly produced stomach acid to break down, so that it does not turn to attacking the stomach walls instead.

Such damage eventually leads to gastric ulcers. The high-fibre structure of roughage means that it must be thoroughly insalivated by your horse. This will allow more saliva-containing bicarbonate to reach the stomach where it will act as a buffer against acid and slow down its effect. Roughage also remains in the stomach for a while. All this does not apply to concentrate feeds, or only to a smaller extent. Concentrates have less structure and therefore do not need to be chewed as thoroughly, allowing it to enter the stomach with less saliva. In addition, the reduced structure of concentrate feed causes another problem: clumps may form in the horse's stomach that are very difficult for the stomach acid to penetrate. Concentrate feeds therefore don't protect the stomach against acidity as well as roughage does.

Now you're probably wondering what this has to do with stress in horses. If your horse is very hungry and practically inhales his feed, please make sure he gets roughage first to ensure a solid basis in his stomach. Of course he can also eat concentrate feed, but, please, only afterwards. The order of "roughage, then concentrates" is extremely important.

Are you interested in the topic of stress in horses? We wrote a whole e-book about it. Learn more here!

Now, we've mentioned vet visits and travel to the veterinary clinic as stressful events for your horse. But the main reason, of course, are the maladies themselves. Colic is a quite common and extremely painful condition. Horses suffering from colic may sweat profusely or roll aggressively on the ground; these reactions are the body's way of trying to cope with the situation. It is also extremely stressful for the horse, which sometimes even behaves much more aggressively. In the case of mild colic, a slow walk can help to take your horse's mind off things and make the wait for your vet feel shorter.

We've already mentioned the problem of hasty feed intake. Another problem can arise if the feed bolus (that's the technical term for lumps) has made it through the stomach, only to get stuck in the bowel. In this case, we are then dealing with constipation, which can eventually result in colic. Treatment can be done in two ways: If the constipation is not too bad, even ample liquid intake can solve the problem. In the worst cases, only surgery can help. Trying to avoid colic in horses is almost a pointless endeavour. But with impaction colic, you have at least a few options to reduce the likelihood of it occurring.

Let's make a small digression at this point. When you aim to make sure that your horse is doing well, and you're learning about what to do or what not to do, you are showing interest in the welfare of your horse – or, in short: you care about your animal's well-being. This has been a subject of much discussion for years, particularly in agriculture. At the end of this article you will find a checklist for stress-free management of your horse. Something similar exists for animal welfare. Well, there are many ways to define animal welfare, but the 5 freedoms are sufficient for you at this point, as you can apply them directly.

-1.png?width=1348&name=grafik%20(1)-1.png)

Stress in horses may not only arise in dealing with the animal, but also in everyday management and through illness. A key factor, then, is prevention. With a balanced diet and adequate drinking water available, you are already doing a lot right. Exercise is also naturally important for your horse. Exercise is often mentioned as a preventive measure in association with colic. After all, your horse's anatomy could stand some improvement despite all its adaptation to life at pasture. The intestine has very few attachments in the abdomen, allowing it to become displaced, which can mean trouble for your horse and, of course, for you. Accumulation of gas, liquid, or clumps of feed can lead to parts of the intestine being pushed into angles where nothing can then pass. Any kind of walking movement by the horse, on the other hand, can prevent exactly that and cause gases to leave the body and the feed to be digested further.

This sometimes tends to be forgotten, but exercise not only helps prevent colic, it is also fundamentally good for horses. Your horse can't stare at the walls of its stable 24 hours a day. It's this feeling of desperately wanting to do something that is not possible that can actively cause stress in your horse.

Always let your horse meet its basic needs for adequate exercise and time spent in the company of other horses. Your importance as a caregiver can't be underestimated here. In fact, you need to be well yourself so that you can both take good care of your horse and be aware of his needs. Ultimately, your horse also just wants to enjoy his time with you. This is another aspect that is often somewhat overlooked: as a human being, you are not an extra who only has to do this or not do that, but a very important part of the relationship between human and horse. Ultimately, stress can only be avoided in a good relationship with each other – or, in unusual situations, at least reduced.

Horses are perfectly adapted to life in the wild. The search for food is easy, the horses practically stand on it while they scan the wide grassland for potential dangers. To ensure that the food can be digested just as spontaneously as it ends up in the horse's stomach, the stomach constantly produces gastric acid. In horse keeping with stables and "human" daily routines, this can sometimes become a challenge. This also applies to the second major characteristic: horses are flight animals. These two characteristics must be taken into account in daily handling in order to avoid stress for the animals.

Equine 74 Gastric

Buffers the excess acid in the horse's stomach instead of blocking it.

Equine 74 Stomach Calm Relax

Supports the nervous horse stomach in stressful situations.