Underrated: Gastric Ulcers in Leisure Horses - The Hidden Stressors

5 min. read time

Audio version – listen to this article easily

You would consider equine gastric ulcers to be rather uncommon, but nothing could be further from the truth. Scientific research shows that 1 out of 2 horses will be diagnosed with a gastric ulcer during their lifetime.

In performance horses, this percentage is considerably higher. For instance, 70% of Endurance horses get a gastric ulcer. In thoroughbred racehorses, with an average of 90%, only 1 out of 10 racehorses does not get an ulcer!!!

A shocking result. But don't be fooled, 36 to 53% of pleasure horses also get ulcers. Continue reading and discover risk factors, clinical signs and possible solutions for the equine health of both foals and adult horses.

B Perron, ABA Ali, P Svagerko, K Vernon, The influence of severity of gastric ulceration on horse behaviour and heart rate variability, J Vet Behav, 59 (2023), pp. 25-29, 10.1016/j.jveb.2022.11.008

A gastric ulcer in the horse (Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome, EGUS) basically results from a lesion of the gastric mucosa.

A lesion is damaged tissue or an injury to the stomach wall lining. This is often caused by stress-related interruption of the renewal of the gastric mucous membrane. Leading to inadequate protection against acidic fluid. In addition, the proportion of acid in the horse's stomach is often too high, because there is not enough feed available to buffer the stomach acid, or eating breaks are too long.

EGUS, Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome, is the general term for gastric ulceration. Within 24 to 48 hours, a mucous irritation can develop into a crater-shaped gastric ulcer.

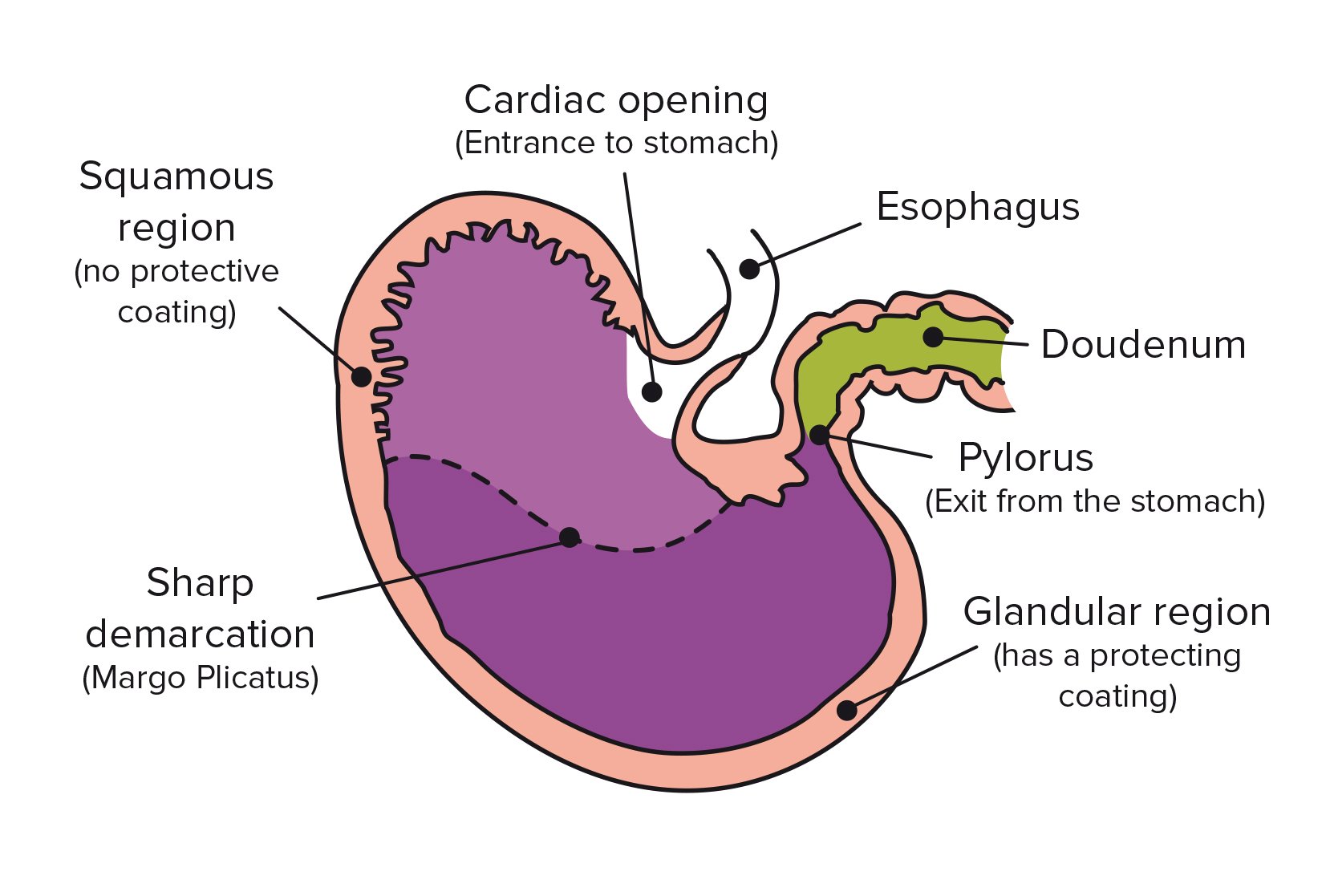

Depending on the physical location, a distinction is made between ulcers in the squamous part (ESGUS: Equine Squamous Gastric Ulcer Syndrome or Equine Squamous Gastric Disease) and the glandular part (EGGUS: Equine Glandular Gastric Ulcer Syndrome or Equine Glandular Gastric Disease) of the horse's stomach.

A lesion may also be localized exactly at the boundary of these two gastric zones. Finally, a gastric ulcer can occur at the gastric outlet (pylorus). Duodenal ulceration in adult horses and foals is considered part of EGUS.

If the gastric mucous membrane production is interrupted, the danger for gastric ulcers in this upper part is largest, so-called squamous ulcers.

Although ulcers are less common in the lower part of the stomach, the glandular region, they should not be overlooked. Mucus producing cells inhibit the influence of gastric acid. Since stomach acid is permanently present in the lower part, it cannot be identified as the sole cause of glandular ulcers. Horses with ulcers in the glandular region are referred to as having Equine Glandular Gastric Disease (EGGD)

The margo plicatus separates the above parts by means of a transition line. Damage also occurs at this border area. Which can lead to inflammation, lesions and ulcers of the stomach wall.

The connection from the stomach to the duodenum, the pylorus, is a fourth location where gastric ulcers occur. Research using gastroscopy shows that there is a proportional relationship between the performance level of horses, the risk of lesions in this area and duodenal ulcers.

For effective treatment of gastric ulcers, some prior knowledge of the anatomy of the horse's stomach and stomach wall is desirable. Horses have a comparatively small stomach, which acts as a conduit to the intestines.

The storage capacity of 15 litres is limited. The entrance to the stomach (cardia) connects the oesophagus to the stomach.

The equine stomach belongs to the compound stomachs, consisting of two parts - the squamous mucosa of the upper part, and the glandular mucosa of the lower part. The margo plicatus separates the two parts in the form of a boundary line. The gastric outlet is called the pylorus and connects the stomach to the duodenum.

Digestive enzymes need an acidic environment. In addition, bacteria and other micro-organisms are killed in this acidic environment of the horse stomach.

Humans cope well with irregular food intake because stomach acid is produced the moment we eat. However, the horse produces these acids 24/7, regardless of the presence of food.

Due to this non-stop production, a surplus of acid occurs if no food ends up in the stomach. As a result, the stomach wall can become irritated. Which is very painful for horses with gastric ulcers.

Stomach acid is extremely powerful and would directly affect the gastric mucosa if it did not have a protective mucus layer.

Things go wrong when we do not mimic the horse's natural nutritional intake well enough. Evolutionary, as herd and step animals, they are continuous eaters. Their stomachs are set to continuously consume a small amount of nutrient-poor roughage.

So that the digestive process does not grind to a halt, stomach acid is produced non-stop. Saliva and feed act as buffers. The feed absorbs, whilst saliva help neutralize stomach acid.

The natural acid-buffer in saliva, bicarbonate, is produced only during the chewing and grinding process. Continuous foraging, as in the wild, maintains the natural balance between bicarbonate and stomach acid.

As a result, horses produce between 40 to 60 litres of saliva a day, mainly by chewing and grinding feeds high in crude fibre. Plenty of horses get two or three meals per day, where large portions are served. Most often horses encounter too little crude fibre, yet too much concentrates. Apart from these few feeding sessions, the stomach has no work to do. This manifests itself in reduced appetite or, on the contrary, obsessive eating behaviour and can cause various problems, such as gastric ulcers.

Housing and nutrition of domesticated horses have changed enormously over the past decades. Too small portions of roughage result in a lopsided stomach's natural balance. Healthy stomach function is compromised.

Overuse of anti-inflammatory drugs is also found to be causing severe ulceration. Lack of free exercise, eating breaks that are too long, irregular feeding times, intensive training, unfriendly "box neighbours", a non-harmonious group composition at the paddock or pasture, and so on, can mean be triggers. But why do horses get gastric ulcers?

According to many vets, stress-related overproduction of stomach acid is the main cause of gastric ulcers. This is actually incorrect, as horses produce them 24/7, so there is no over-production. It is rather the bare emptiness of the stomach that causes problems. Lack of (low fibre) food. Stomach acid itself is not bad; the horse's stomach is quite resistant to and even dependent on them.

Stomach acid plays an important role in digestion: it is absorbed by food - regardless if it's hay / oats or concentrates - and in combination with saliva, produced during chewing, the digestion in the stomach starts. Furthermore, it kills bacteria.

But as always, the dose determines the poison! Many horses have an abundance of stomach acid because not enough roughage is fed, as a result the unprotected upper stomach wall can be damaged. Worst case scenario is when there is no food at all present in the stomach, the acid dances around like a small lake, damaging the mucous membrane.

Especially at trot and gallop, horses show discomfort and pain. Therefore, you should not ride your horse on a (roughage) empty stomach. Stress has another influence: cortisol levels increase during stress. There is decreased blood flow towards the stomach, making the stomach wall less nourished, more sensitive to acid and less capable to regenerate.

Irritation of the stomach lining causes abdominal pain, resulting in the horse experiencing even more stress. This creates the risk of a vicious circle. Physical and environmental stressors should therefore be avoided as much as possible.

Illness, lameness, pain, a strange environment, being in the stable for long periods, stall confinement, transport, surgeries, but most certainly also unpredictability and lack of routine create physical and environmental risk factors for most horses and thus increase the risk of gastric ulcers.

Because, unfortunately, many horse owners discover too late that the diet or housing is not optimal for their horse's equine health, gastric ulcers usually go unnoticed at first. Even after successful treatment, the ulcers return. Food and housing adapted to the type of horse are essential in preventing gastric ulcers.

Above all, this means that a horse must have sufficient high-quality roughage available. Supplemented, if necessary, by suitable mineral feed. To ensure high saliva production to buffer stomach acids, and decrease the risk of squamous ulcers, long feeding breaks and irregular feeding times should be avoided.

Mimicking natural feed intake as much as possible will also benefit horses in current housing systems. In addition, there are special feeds and supplements that can accurately support the horse with a sensitive stomach or stomach ulcers.

In general, it is advisable to feed a horse roughage before feeding concentrates. Divide sufficient roughage into as many portions per day as possible. Or even provide unlimited roughage. Because the shorter the breaks in between eating are, the lower the risk of excess acid that can damage the stomach wall. The norm for sufficient roughage is at least 1.5% of the desired (!) body weight in dry matter, per day.

What about Alfalfa hay?

Alfalfa (lucerne) hay can, on the short term, substitute hay or other roughage, as it will certainly stimulate saliva production compared to high grain diets. Some research suggests that the sharp structure of chopped alfalfa does not have a particularly positive effect on the gastric mucosa, but rather causes mechanical irritation of the gastric mucosa and thus gastric mucosal lesions.

Therefore, alfalfa, which in itself is a high-quality food plant for the horse, should preferably be fed as a pellet or extrudate. Unfortunately, high levels of lucerne hay or chaff may not be desirable for some horses due to its high calorie, protein, and calcium levels. Always have an equine nutritionist review your horses’ diets to ensure the best combination of feed and forage for their age, weight, breed, and workload.

An unfamiliar environment, stall confinement, strange scents and a horse that generally does not feel top notch. Clinic stays generally involve a lot of stress.

In addition, a horse needs to be sober, at least 12 hours without food and 6 hours without water, before an examination or surgery can be performed. In the case of gastric ulcers, where the stomach is examined by gastroscopy, this is counterproductive in the thoughts of many horsepeople. But sometimes this is the only way, to figure out about the grades of gastric ulcers.

Luckily, visiting a clinic, undergoing an extensive check and treatment with medicines, are in most cases not the only solutions possible.

Horses that have to perform during intense exercise do not eat for several hours during that training. As a result, not enough saliva enters the stomach, hence the acid is not buffered.

This can cause damage to the stomach lining and ultimately stomach ulcers. Pay attention to regular breaks between training sessions, as during exercise digestion is virtually shut down.

There is also an increased abdominal pressure during intense exercise. This pushes the acid up into the stomach, making it easier to damage the squamous region.

Based on certain symptoms, you suspect your horse has a gastric ulcer. By an endoscopic examination your vet can perform a gastroscopy to determine whether your suspicion of an equine glandular gastric disease is correct.

The main and most common clinical signs of equine ulcers are:

1. Poor appetite: Horses with stomach problems generally have poor appetite. They spill feed and ignore it. In short, your horse eats with less enthusiasm. This is partly because it is very painful when the inflamed parts of the stomach come into contact with acids.

2. Weight loss: Due to reduced feed intake, the organism is no longer supplied with sufficient energy and nutrients, body weight decreases. Weight loss and poor body condition will be the first things you notice.

3. Colic. Recurrent colic, intermittent colic, or even vague colic complaints: The horse stands with its belly raised after eating (concentrate feed), looks at its belly, lies down, rolls and stands up again. These positions seem to provide some relief from severe gastric ulceration.

4. Dull coat: Not every horse with gastric ulcers has a bad coat! Many horses suffering of severe ulcers have a shiny coat and appear externally healthy. Sometimes, due to the disturbed metabolism, sufficient nutrients are no longer available and the coat loses its shine - hence the dull coat.

5. Poor performance: Stomach pain and reduced nutrient absorption can lead to a drop in performance levels. The horse does not have enough energy to do the job.

6. Yawning more often: If a horse yawns constantly, it is a relatively clear indication of disorders of the gastrointestinal tract. On the other hand, horses yawn to lower their stress levels. If horses with gastrointestinal complaints or severe ulceration have anything in abundance, it is stress - either as a trigger for the gastric ulcer and/or as a result of pain.

Other symptoms may include flehmen, cribbing, isolation from the herd, a girthy horse, increased saliva production and tail swishing. See also: 21 main symptoms of gastric ulcers in horses. Download our E-Book for free!

Apart from recognizing clinical signs, the only way to make a definitive diagnosis is through a gastroscopy. This involves the vet inserting an endoscope through the nose into the stomach. This allows the oesophagus, the inside of the stomach and the first part of the (small intestine) to be inspected.

The number, severity and type of stomach ulcers can be diagnosed this way. Subsequently, it is often difficult to find out what the exact cause was.

Stomach ulcers hurt. Besides optimizing husbandry, feeding and training systems, you can treat horses with ulcers with certain drugs or support them with supplements. Three types are distinguished here.

1. Stomach acid binders or buffers: also called antacids, are alkaline substances that buffer the acid already present. Buffering means increasing the gastric pH value and thus reducing the stomach's acidity. Another advantage of these buffers is that the feed obtains a better pH-value. This is very important for the further digestion and metabolism in the (small) intestine(s). Equine Gastric 74 belongs to this group.

2. Antacids: e.g. Omeprazole (paste). These have the ability to block and inhibit up to 99% of the acid production. This acid suppressive therapy is known for its ability to treat severe gastric ulceration in all types of horses. The damaged stomach wall is given a chance to regenerate. However, be careful with long-term use of these painkillers and other anti-inflammatory drugs, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

3. Gastroprotectants: Form a layer on the mucous membrane, protecting the stomach wall from acid. Sucralfate is a well-known stomach wall protector.

Apart from stomach acid binders, there are natural alternatives to maintain a healthy stomach. To some extent they might even help protect the horse's stomach. Dietary supplements based on pectin and lecithin are especially suitable for this purpose, as they support the natural protective mechanisms of the stomach lining.

Just like flaxseed, which contains a particularly high content of mucilage. Some feeds can also support your horse's ulcer healing.

The symptoms of a horse with gastric ulcers should visibly diminish within three to four days when treated with medication. This does not mean the ulcer is cured!

If the ulcer is not completely healed, you often see a relapse as soon as you stop medication. Therefore, it is wise to have another gastroscopy after at least 1 month to check.

Can a horse's ulcer heal by itself?

No, the vast majority of cases do not heal spontaneously. Your horse will need external help treating ulcers, either with medication or natural products.

Preventing stomach ulcers in horses

There are some basic rules, including dietary factors, when it comes to preventing gastric disease. The 5 most important points to prevent gastritis and stomach ulcers in horses:

For further information on feeding your horse, don't forget to explore our E-Book section. Here, you can access our exclusive Feeding ABC guide for free and discover valuable insights to keep your horse nourished and thriving.

Equine 74 Gastric

Buffers the excess acid in the horse's stomach instead of blocking it.

Equine 74 Stomach Calm Relax

Supports the nervous horse stomach in stressful situations.